Kheti par kiski maar? Jungli janwar, mausam aur sarkar. Throughout the 1980s, this thought-provoking slogan resonated with farmers across Uttarakhand in the aftermath of the green revolution.

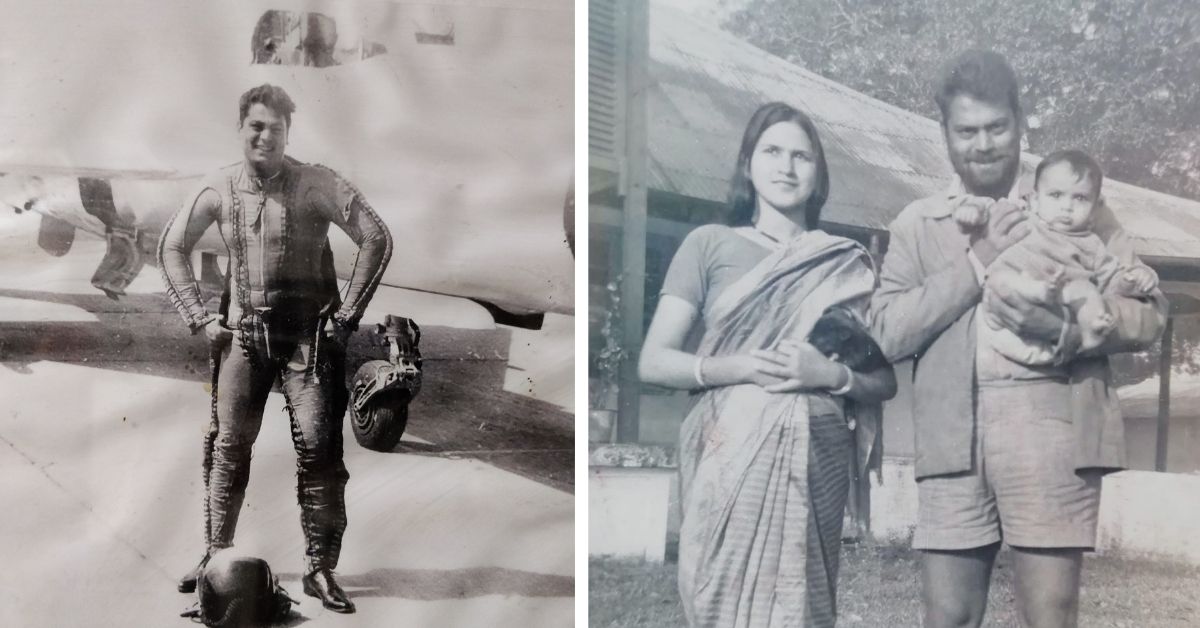

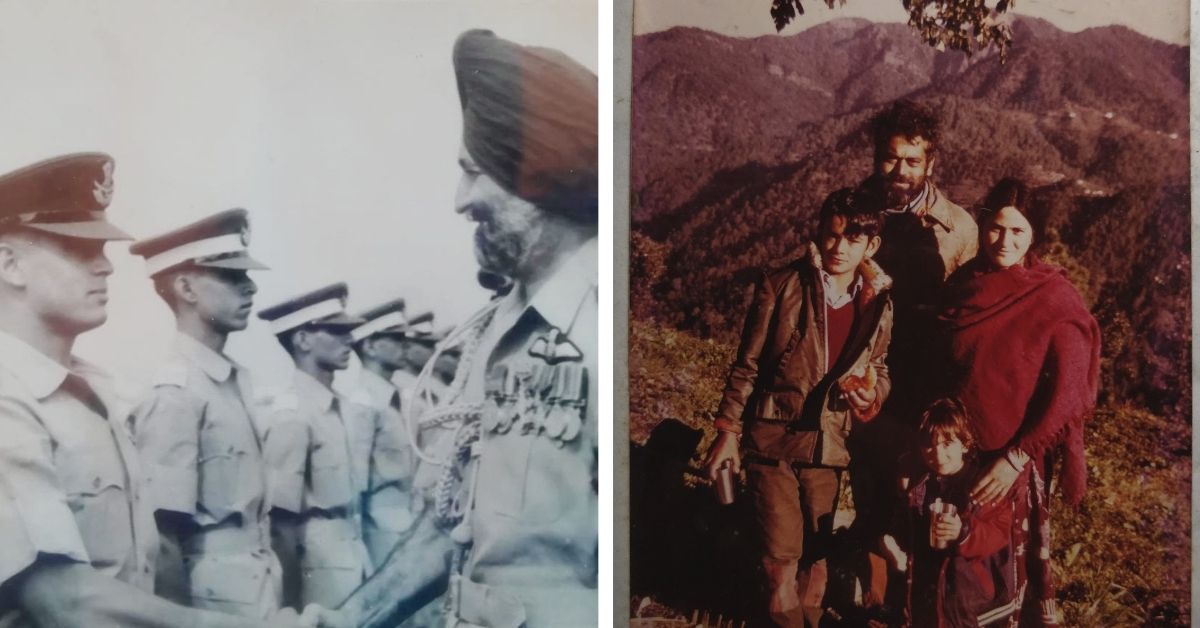

Led by the founder of Beej Bachao Andolan (Save Seeds) (BBA), Vijay Jardhari, the pan-state movement was against monoculture farming and forceful replacement of nutritious cultivation like millets with cash crops.

Vijay, whose family had been cultivating multiple varieties of crops for generations, predicted the long term repercussions of monoculture or growing a single crop on soil fertility and subsequently the rise in farmer distress.

While growing up he had seen the health and environmental benefits of growing more than one traditional crop in the same land. So, when the government was giving soybeans and chemical fertilisers at dirt cheap rates, it did not go down well with Vijay and he started BBA to conserve traditional varieties.

Most people from the agricultural field are aware of Vijay’s Dandi march across the state with his friends to collect indigenous seeds (he collected 350 varieties of seeds!).

However, very few know that while knocking on every farmer’s doorstep, Vijay ended up sharing his knowledge on an ancient farming practice called ‘Baranaj’ (Bara is 12 and Anaj means crop).

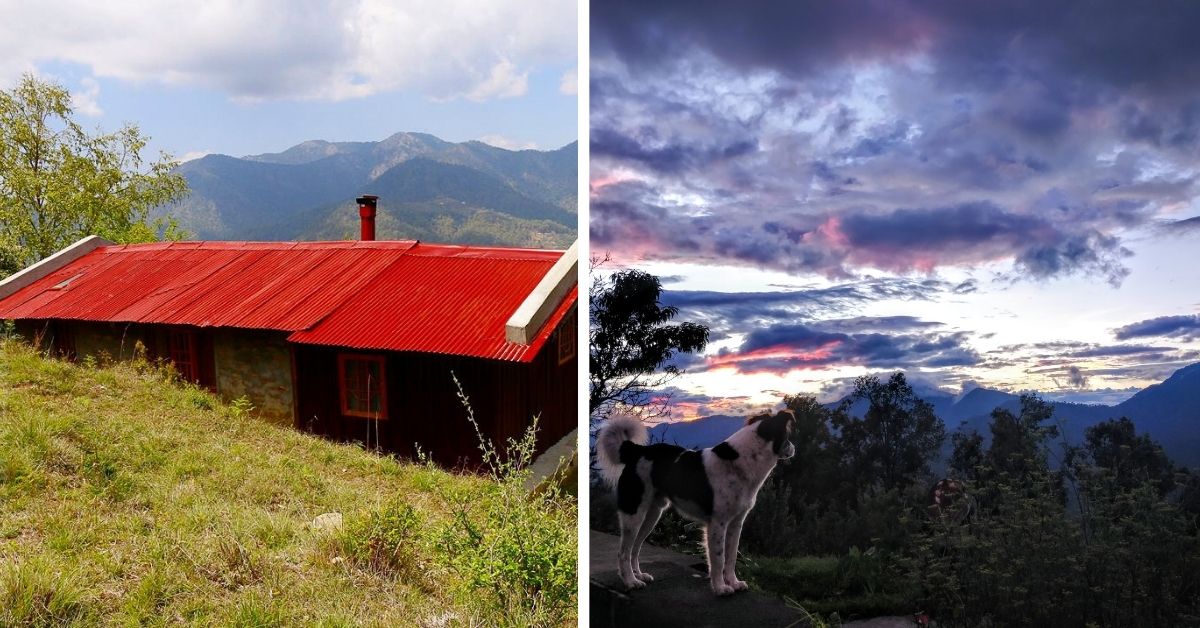

“It is an inter-cropping method of twelve or more crops that is usually practised in rain-fed Tehri-Garhwal regions. It gives a farmer a wholesome land on which lentils, cereals, vegetables, legumes and creepers grow in harmony with each other. For example, stems of grains act as a natural support for creepers of legumes. Once the key to the success of our ancestors, this method was dying in the 80s. It provides food security to the farmer and also raises soil fertility,” Vijay, who is now in his late sixties, tells The Better India.

I spoke at length with Vijay, who was conferred with Indira Gandhi Paryavaran Puraskar in 2009 for his exceptional contribution to saving traditional seed varieties via BBA, to understand baranaj and its benefits.

Baranaj: Process & Specifications

One of the major advantages of this method is that a farmer will never have to worry about going hungry or taking a hefty loan.

“Some of the crops in the cycle are resistant to drought, pests, and floods so during a natural calamity, even if some crops are damaged, he will still get enough food to sell in the market or for self-consumption. Additionally, the baranaj process is similar to that of forest and hence it does not require any chemical inputs or excessive irrigation. They are all rainfed. Maintaining diversity in plants also boosts soil fertility and it provides varying fodder options for farm animals,” explains Vijay.

According to him, there is no fixed pattern or combinations that a farmer has to use as long as the crops are a mix of grains, masala, vegetables and pulses.

Vijay’s recommendation:

- Grains: Mandua (finger millet), jowar (sorghum), ramdana (amaranthus), kuttu/ogal (buckwheat), and corn.

- Pulses/beans: Rajma, lobia, bhat (black soybean), naurangi (rice beans), urad and moong.

- Vegetables: cholai (Amaranth), kheera, ogal (local variety) and lobia (black-eyed beans)

- Spices: sesame and til (sesame)

Identifying companion seeds that will boost each other’s growth is very important for a farmer.

“Roots of jowar hold the soil and prevent erosion during floods. Meanwhile, pulses like lobia or naurangi can provide nitrogen to other vegetables like cholai and cabbage as these need a lot of nutrients. Millets are rainfed crops so its roots will absorb all the excess water and prevent floods. All these plants will have different heights so the tall ones can provide shade during extreme heat,” he explains.

Apart from being safe from extreme climatic conditions and being companions to each other, the crop rotation will also ensure that wild animals and birds do not destroy the entire field. For instance, birds feed on jowar so Vijay keeps aside a portion just for them. In return, birds help in maintaining bio-diversity.

Since crops are rotated on an annual basis, insects thrive less on the field and to prevent pest attacks, Vijay suggests using manure made from cow’s dung and urine. This way, a farmer will save on external chemical inputs.

Baranaj Could Be Zero Budget

With his budget-friendly tips and effective yield practices, Vijay has inspired thousands of farmers to start baranaj in the last 30 years. The majority of farmers from 15-20 villages around his village follow this method.

This is because the investment cost is considerably less in a world where farmers are at the mercy of expensive fertilisers.

“Maybe in the first rotation, you have to rely on the market for seeds but after that, you can save some seeds and replant them every year. We still follow the barter system ritual where if one of my seeds is not giving proper yield, I will exchange it with another farmer in a similar situation. This way both of us can try new seeds and in most cases, this works. This a great way to save money,” Dhum Singh Negi, a Senior Chipko leader from Vijay’s village tells The Better India. Negi has been practising baranaj for the last 60 years.

This understanding and harmony is also reflected when it comes to labour work. Instead of hiring labour, a group of farmers help each in the sowing process, “Sowing seeds is no less than a festival for us where we take dhols and drums in the fields and even dance while sowing. This ritual helps us stay united,” says Vijay.

Now that a farmer has saved on pesticides, labour and seeds, the inputs costs are almost zero.

‘We Can Prevent Farmer Suicides’

A farmer’s inability to pay loans coupled with erratic climatic conditions often pushes him to take extreme measures including suicide. The situation is worse for farmers with small landholdings who are unable to produce a higher yield.

Succumbing to the pressure, the farmer ends up using more chemical fertilisers to artificially increase the production and in turn compromises with the crop quality and soil fertility to an extent where the land altogether disrupts the cultivation cycle.

To break this vicious cycle, both Vijay and Negi vouch for the baranaj.

“Our ancestral knowledge has helped us become atmanirbhar (self-reliant) as I no more have to rely on any external inputs. It will be hard for a farmer to switch from monoculture and may even suffer crop damage in the beginning. But in the long run, they will benefit. By promoting this method, we can prevent farmer suicides. The best part? A farmer will not be affected by jungli janwar, mausam and sarkar,” Vijay concludes.

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)